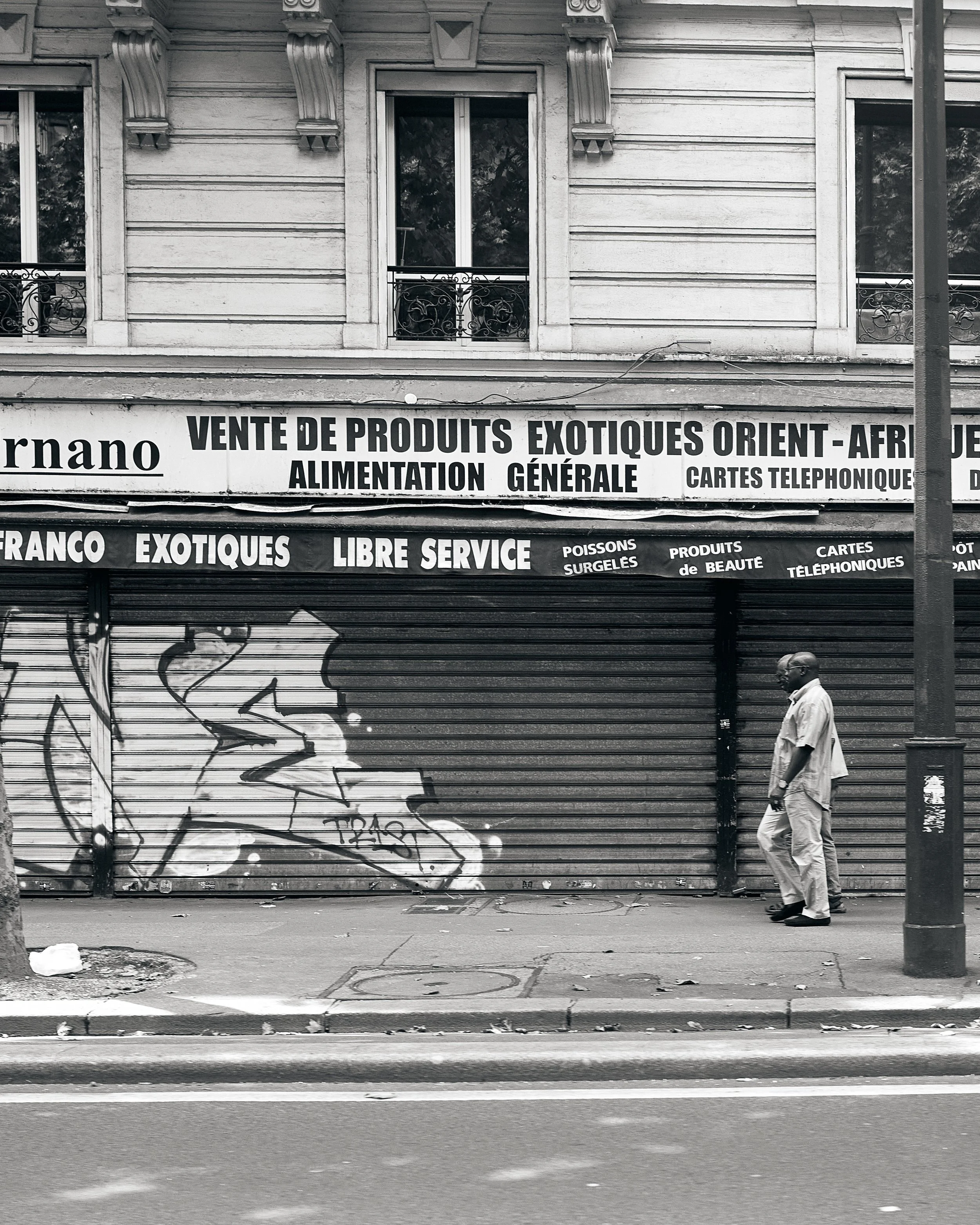

What they say about Parisians is true, they are effortlessly stylish. Stepping off an overnight bus from London, and popping out into a crisp early morning Autumn rush-hour in Paris, the hour-long journey through the streets of Paris, from the southern side at the bus stop to Montmartre in the north, made for a softly lit exploration of daily life in Paris, through the eyes of an Uber window.

--- All That Glitters is Not Gold (it’s Plastic): Plastic Pollution on World Heritage Listed K’Gari ---

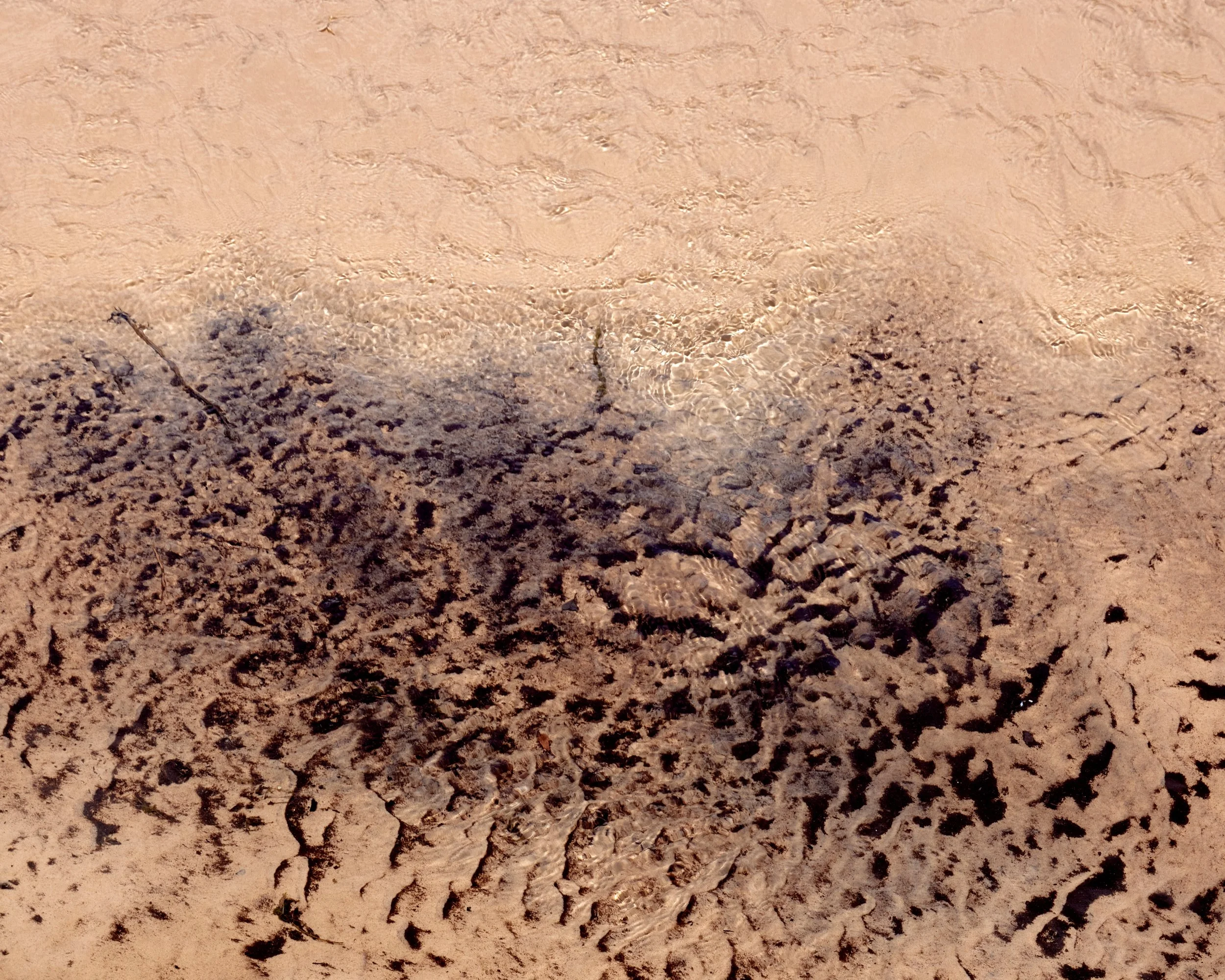

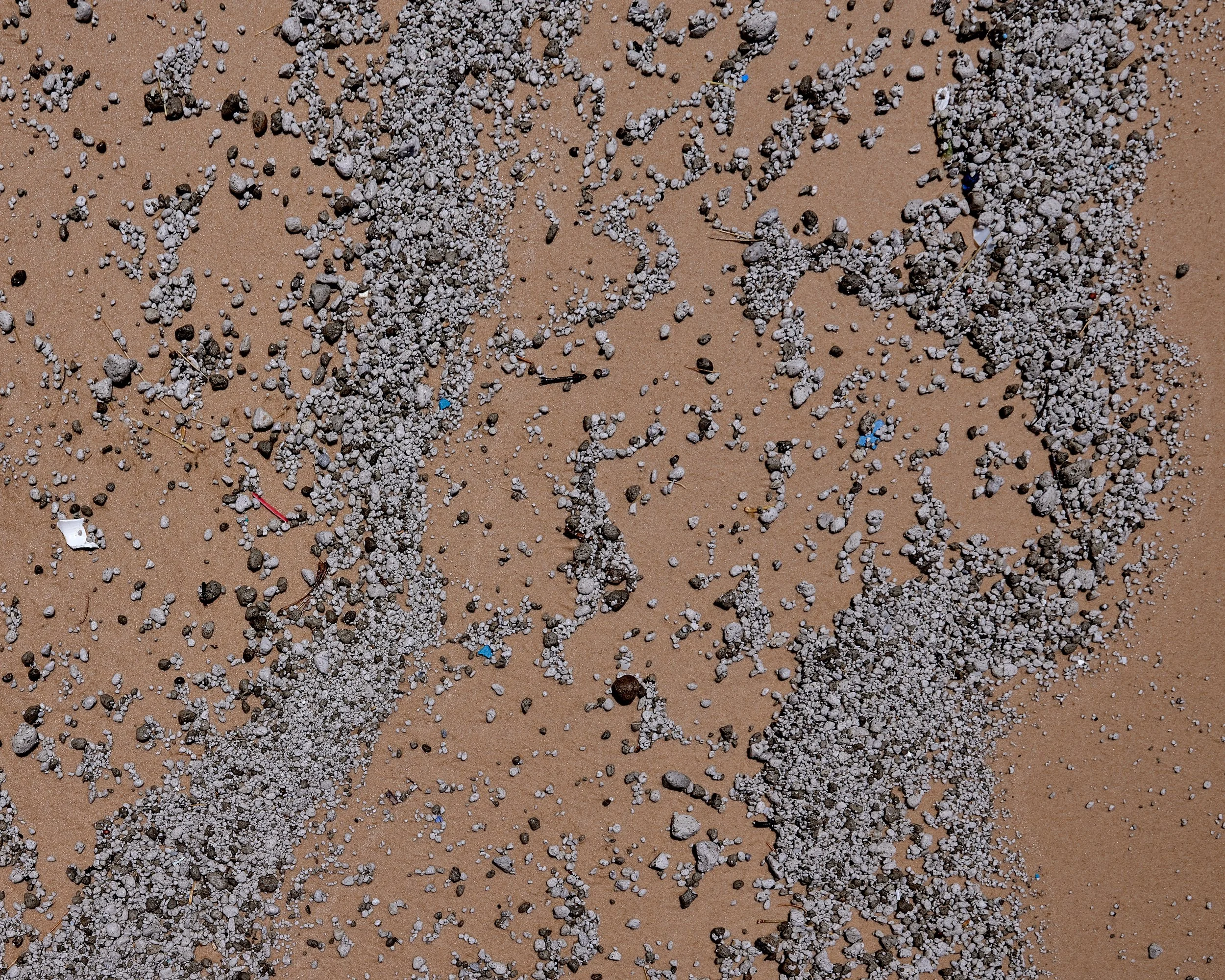

As I gaze over the myriad of different layers of of different sized ripples in the sand, sparkling in the afternoon light, the awe and dissociation I was feeling was abruptly interrupted by the realisation that what I was looking at was not only a natural phenomenon of light reflecting off crushed sea creatures but also the harshness of light bouncing off plastic.

Those brightly coloured “shells” I had admired from the corner of my eye were not only the magical coral I had imagined but were tiny pieces of esky and other quintessential Australian camping items broken off into the sand. On closer inspection they were in every section of the beach and every photo I took of the sand.

K'gari (/ˈɡɑːri/ GAH-ree, lit. 'Paradise'), also known by its former name Fraser Island, is a World Heritage-listed sand island along the south-eastern coast in the Wide Bay–Burnett region of Queensland, Australia. K’gari is one of the world’s natural treasures. With its vast dunes, unique freshwater lakes, and rich Indigenous heritage, it stands as a paradise for adventurers. Each year, up to 500,000 people are drawn to its shores to camp, hike, and experience the island’s rare and diverse ecosystem. However, as more people come to appreciate its beauty, a disturbing reality becomes increasingly visible: the plastic pollution left behind by visitors. This pollution not only disrupts the landscape but endangers the island’s unique flora and fauna, threatening to scar K’gari’s delicate ecosystem permanently.

Plastic pollution on Fraser Island comes in many forms: discarded water bottles, food wrappers, plastic bags, cigarette butts, and even larger debris washed up from boats or other coastal areas. Though these items may seem small in isolation, collectively they form a devastating layer of contamination that affects the island’s pristine beaches, lakes, and inland forests. Plastic, due to its durability, does not decompose for hundreds of years. As it breaks down into microplastics, it becomes even harder to clean up, embedding itself in the soil and water, where it is nearly impossible to remove.

Wildlife is often the first victim of plastic pollution. K’gari is home to many native species like dingoes, goannas, and a range of marine life that rely on the island’s ecosystem. Animals can mistake plastic items for food, ingesting them and, in many cases, suffering fatal consequences. Plastic waste also disrupts plant life, contaminating the soil and reducing its ability to support local vegetation. This pollution impacts the entire food web, posing serious risks to the health and survival of countless species.

Beyond the ecological impact, the plastic waste on K’gari tarnishes its cultural and spiritual significance. The Butchulla people, the island’s traditional custodians, have lived in harmony with the land for thousands of years, maintaining a deep respect for nature and its cycles. Plastic pollution desecrates their sacred lands, eroding the cultural heritage of this World Heritage-listed site and undermining the teachings that promote respect and stewardship of the environment.

The sad truth is that this pollution is preventable. Each piece of plastic represents a choice, whether it’s a bottle cap left behind at a campsite or a plastic bag blown into the dunes. As travellers, we are responsible for ensuring that our enjoyment of nature does not come at the expense of its preservation. Small actions like bringing reusable containers, packing out all waste, and participating in local clean-ups can make a big difference. Awareness campaigns are also crucial; they remind visitors of the fragile beauty of Fraser Island and the importance of leaving no trace.

As stewards of K’gari, we must ensure that the island remains pristine for generations to come. This requires not only personal responsibility but also collective action to protect and preserve the beauty of this natural wonder. If we do not change our behaviours, the damage could become irreversible, not only on Fraser Island but across all places where nature meets humanity.

What are the alternatives?

Here’s a list of eco-friendly camping products to help reduce plastic pollution while traveling, especially in sensitive environments like Fraser Island (K’gari):

Reusable and Sustainable Essentials

Stainless Steel or Bamboo Utensils

Collapsible Silicone Food Containers

Beeswax Wraps

Reusable Water Bottles and Filters

Mesh Produce Bags

Portable Cutlery and Straw Sets

Eco-Friendly Cooking and Cleaning Gear

Biodegradable Soap and Sponges

Compact Solar-Powered Cookers

Reusable Coffee Filters or Presses

Eco-Friendly Personal Care Items

Solid Toiletries

Reusable Silicone Travel Bottles

Compostable Toothbrushes

Eco-Friendly Waste Management

Portable Trash and Recycling Bags

Trowel for Responsible Waste Disposal

Lightweight trowels made from recycled materials encourage responsible disposal of organic waste (following Leave No Trace principles).

Compostable Trash Bags

Sustainable Camping Gear

Recycled Fabric Backpacks and Tents

Solar-Powered Lanterns and Chargers

Recyclable Camping Stoves

Smart Alternatives to Single-Use Products

Eco-Friendly Fire Starters

Fabric Napkins or Towels

Tips to Maximise Impact

Plan Ahead: Buy in bulk and prepare meals to reduce the need for packaged food while camping.

Leave No Trace Kits: Carry a small kit with reusable items like gloves, trash bags, and tongs to help pick up litter.

Support Ethical Brands: Look for camping gear from companies committed to sustainability.

By incorporating these eco-friendly products, campers can minimise their environmental footprint and contribute to the preservation of beautiful places like K’Gari.

--- People and Place - The Colours of Africa ---

Across Africa, colour is woven into daily life with effortless grace. In Ghana and Tanzania especially, the vivid textiles worn by the people often mirror the painted walls, shopfronts, and weathered streets around them. This photographic essay captures those moments where dress and environment seem to speak the same language, whether by chance or quiet intention. From bold kente patterns in Ghana to the flowing khangas of Tanzania, each image celebrates the harmony between people and place, revealing a living canvas where tradition, identity, and beauty move together in rhythm.

--- Rubble and Dust - Katmandu 2018 - 3 Years after the Earthquake ---

Rubble and Dust

In 2018, I travelled to Nepal and lived there with family for around five weeks. At the time, I found it a difficult country to travel in, dry, dusty, bumpy travel, with extremely poor air quality. I had been travelling already for around seven months and I was tired. On reflection, the beauty of the discomfort really shines through, and the obvious reasons for the discomfort I experienced lie purely in the socio-economic effects of natural disasters on developing countries. I travelled to Kathmandu three years after the Gorkha earthquake, and the level of destruction and rubble that was still evident on every corner was confronting. However, it is the rubble and dust filling the streets and air, which brought a magical haze to the city at dawn and dusk, that created the discomfort but also the beauty in the imagery.

To give you an idea of how polluted the city is. Kathmandu lies in a valley surrounded by the Himalayas, so you can imagine how deep that valley is, and how trapped pollution could get in a bowl situation like that. I was in Kathmandu for one month before, I even saw the Himalayas from the city because of the deep, thick smog, which constantly blankets the city. In some of the images, you can clearly see the blanket hovering over the city, If you’re lucky you will see the mountains pop through the blanket which is quite a sight to behold, but also makes you painfully aware how thick the blanket really is to be able to block out such gigantic objects most of the time!

In the car on the way back down into the city, the transition from mountain air to city smog is almost impossible for the lungs to adapt to. It is thick, textured and flavoured.

Rising pollution levels have made the city one of the world’s most polluted, exacerbated by dry weather and urban dust. According to the https://www.iqair.com/au/world-air-quality-ranking website

Kathmandu’s air ranks at the 9th most polluted city in the world.

Structural damage has left many buildings leaning at odd angles, sometimes visibly unstable, sometimes braced with temporary bamboo supports. Building codes, and unchecked construction practices have contributed to the instability of structures, but it is also this fact with brings interest and beauty to the subject matter.

Residents continue to navigate narrow lanes lined with unstable facades. Markets bustle amid rubble and dust. The city’s resilience is interwoven with its scars and the beauty flows freely amongst the chaos.

--- Brutalist Architecture in Okinawa Japan - 2024 ---

I travelled to Okinawa, expecting the best seafood in Japan and tropical beach resorts, this is what I got and enjoyed very much, however, I was also confronted with the onslaught of an impending typhoon. This was disappointing but in the end turned out to be one of the most interesting revelations for me creatively and politically.

I would like to start this essay by saying FUCK THE WAR and FREE PALESTINE!!!

Not only were we faced with the onslaught of a giant storm, but we had booked accommodation on the other side of the island (which we thought was a lot smaller) and turned out to have a five-hour, city-traffic bus ride ahead of us. This journey gave me plenty of opportunity to see the architecture across the island and quite frankly, at first, I was shocked. The buildings looked shabby in the rain and they didn’t seem to have that beautiful Japanese attention to detail that you find in the rest of Japan. After a little investigation as to what had occurred on the island and why it looked the way it did, it all pieced together. I was suddenly in awe of the way the Japanese had dealt with an incredibly sad and tragic situation and still made it as aesthetically pleasing as possible. Concrete brutalist architecture, mixed with the environmental damage from the typhoons and general humidity and wetness on the island made for the perfect dirty walls series and I was feeling right at home.

The holiday had transformed from a relaxing tropical getaway to an in-depth photographic study of Japanese Brutalism and I was not mad about it. The way that Japanese people are able to incorporate design into every aspect of their lives and make the lines flow from any angle is truly amazing to me. It’s very aesthetically pleasing and I find these images to be something like a dirtied-up Wes Anderson film.

Okinawa’s brutalist architecture, with its heavy use of concrete, is uniquely suited to withstand the island’s intense weather conditions, including frequent typhoons. The thick, unadorned concrete walls resist the harsh winds and heavy rain that accompany these powerful storms. Over time, the weather leaves its mark on these structures—eroding sharp edges, staining surfaces with rainwater streaks, and cultivating a rugged patina that speaks to the resilience of both the buildings and the people who inhabit them. Witnessing these structures at the height of a Typhoon highlighted the interconnected beauty of the occupation and the force of nature.

This photographic essay explores the unique blend of raw materiality and cultural context in Okinawa's brutalist structures. Through a lens that captures both the imposing forms and the subtle interactions with their surroundings, the images reveal how these buildings reflect the island's history, identity, and the passage of time.

What happened in Okinawa, Japan, to make it look the way it does today?

During the Battle of Okinawa in 1945, one of the most devastating and bloody battles of World War II, the island suffered immense destruction. Approximately 90% of Okinawa’s buildings were either completely destroyed or severely damaged, including countless traditional structures. This large-scale devastation not only led to the loss of lives and homes but also to the annihilation of much of the island’s architectural heritage.

The relentless bombing and shelling by the American forces during the battle led to the near-total destruction of Okinawa’s traditional homes, temples, and cultural landmarks.

Today, only a few examples of traditional Okinawan architecture survive, The loss of original structures represents a significant cultural scar.

The American occupation, following the battle, introduced new architectural styles and building materials, further altering the island’s landscape. Concrete and Western-style buildings replaced the traditional wooden structures, contributing to the transformation of Okinawa’s built environment.

Traditional Okinawan buildings, known as Minka (民家), were characterized by their wooden structures, red-tiled roofs, and use of local materials like coral limestone. These homes were typically low to the ground, designed to withstand Okinawa’s frequent typhoons, with wide eaves to protect against the rain and open layouts to facilitate airflow in the island’s humid climate. These structures were a vital part of Okinawa’s cultural identity, representing a way of life deeply connected to the natural environment. You can only imagine what the island would look like today if America hadn’t bombed the shit out of this place and then kept a sizable presence there for the foreseeable future.

As of January 2025, approximately 26,000 American soldiers are still stationed in Okinawa. They are occupying the most beautiful beach on the island and there is no access for locals. From what I gathered, the American occupation is a fairly unspoken topic in Okinawa because the Japanese people are turning a blind eye and want to keep the peace, they are after all one of the most polite countries I have visited.

I commend the people of Okinawa for doing their absolute best to keep their culture alive with the ongoing presence of their invaders still with them after all these years.